|

| North Face of Pt. 4250+ from North Ridge Osborn, looking into East Fork Grand Union Creek, Johnson's Tower at left. |

Franklin Johnson, failed mining engineer, now roustabout in the Nome diggings, sat wearily down on his load of redwood planks. The trolley lay sunken in the muck of Grand Central Valley for the fifteenth time that day. Green layers of swamp buzzed and chirped all around the miner, a stout man of Scandinavian descent. Might as well take off this damn harness, thought Johnson, unbuckling a leather strap around his waist. Just like a dog. They had tried a couple of horses to haul the lumber up the valley, then a team of dogs, but the quicksand of Grand Central had sucked the rigs down every time. In the end, the best solution was for one, stout man to wheedle the 16 ft. planks through the swampy sections, inch by inch, sometimes piece by piece, along the makeshift road the men had fashioned along a line of bluffs. Johnson had discovered if he used the planks themselves as shaft and handle of the cart, the hauling wasn't too bad.

|

| Northeast Cirque of Osborn. Weird story about this camp... I hiked up here last July, 20 Saturdays ago. When I got up to this place at the very top of the valley, I had time to kill, so I spent a ridiculously long time choosing a tent platform. I walked around for an hour examining various patches of tundra like a choosy homebuyer. Even after I had selected a tent platform, I kept fussing around with the tent's orientation like an anal-retentive furniture arranger until I felt quite silly about myself for being so particular, when real climbers are supposed to flop down on any surface whatsoever and just sleep on it. When I finally got the tent where I wanted it, I was surprised to find one, buried, aluminum, SMC, tent peg at the exact corner of the tent. This is not a major campground we're talking about here, but seemingly empty wilderness. The tent peg does support the general hypothesis that Grand Central has, at times in the past (as so many places in Beringia) seen a greater population than it does at present. |

The sound of the hammer turned his thoughts back to their project: the Wild Goose Pipeline. "Plunger," cursed Johnson out loud, and spat. "Das ist bescheuert." The engineer in him did not subscribe to the notion that the pipeline would add "head" to the entirety of Nome's ditch system. Misapplication of the Darcy-Weisbach, he thought scornfully. Not only that, but the other crew, the Campion Ditch boys, in a friendly spirit of competition, had confused the mathematics: by ingeniously contouring their open ditches up Buffalo Creek, they had achieved an apical elevation higher than that of the Wild Goose. Like all the miners in the Nome diggings, Johnson was passionate on the subject of ditches. A miner in these hills would as soon dig a ditch as open a can of beans.

To say Johnson was a failed engineer was disingenuous. His true knowledge and expertise belied his lowly position as laborer. Johnson's only failure was his final exams at the Technische Hochschule back in Germany. Or, rather, the night before his final exams.

The American, Perry-Smith, had showed up in his Bugatti, with Petrus in tow. Off the three had sauntered for a night of drunken, moonlight rock climbing on the Elbsandstein. Exams had not gone well for Johnson the next day. With no pedigree to show for all his studies, Johnson boarded a steamer for North America soon thereafter.

|

| Northeast Face Mt. Osborn (Pk. 4714) The dark slash at center of photo is the infamous Sluicebox Couloir. |

There was a woman at Thompson Creek. An honest to god, living, breathing, female. Her presence filled the entire, ten-mile long, Grand Central Valley like a cloud. One of the Osborn brothers had "imported" a wife from Sweden. Against everyone's advice, Osborn had built her a tent cabin to live in for the summer in the moraines of Thompson Creek. Now she was all Johnson could think about as he grunted and sweated over his damn trolley of wood. Jimminy, I don't even know her first name, thought Johnson. He found himself rehearsing the witty things he would say to her. The last time he had passed through, she had invited him in for tea, where they had discussed Shakespeare and Goethe while her husband labored above them on the hill. She had mentioned she craved some running water at her cabin door--Maybe I'll just pick up a shovel and knock out a quick ditch line for her, thought Johnson, it wouldn't be any trouble at all.

But when Johnson finally pulled up to the encampment, the poor woman was already besieged by admirers. Two men were seated on crates outside her cabin, a new kid, and that Irish pensioner whose name Johnson could never remember. From behind the tent flap she emerged, not the beauteous, flaxen-haired maid from Johnson's memory, but the same woman, transformed, apparently, by a week of backcountry living. Her bonnet was torn and muddy, her face swollen with mosquito bites, her dress blackened with soot. Her cheeks bulged with chaw, and she commenced to cussing up a blue streak with the two miners.

Something had changed. Johnson was disillusioned. The pensioner was carrying on at great length. This guy probably just hired on with Wild Goose for doctor benefits, thought Johnson, but said nothing. Instead, sat down and loaded his corn-cob.

|

| Looking west up Thompson Creek from the terminal moraines of the extinct Thompson Creek Glacier. A plethora of planks and ancient cabin frames is my evidence that this spot was inhabited during Wild Goose Pipeline days. |

One item of conversation, however, had filtered through Johnson's attention: the Irish claimed to have "prospected" up the North Fork of Grand Central the week before, and passed over Mt. Osborn to the Cobblestone River, just up the valley.

Johnson had launched vigorous inquiry; "D' right fork, you're sure? To d' right o' Osborn? On der gletcher? Chu made it to d' Cobblestone?"

"Aye, the right fork it was,"the pensioner had assured him.

Now, Johnson, on prior occasion had poked around the North Fork himself: he knew there was nothing around that bend but huge, unscalable, limestone walls. No way that little Irish dude had scaled Mt. Osborn from the north. Not even Fehrmann would venture up onto those verscheissene walls. Nevertheless, Johnson had resolved right then and there to hike up to the glacier that very afternoon, to check out this pensioner's claim of a crossing.

|

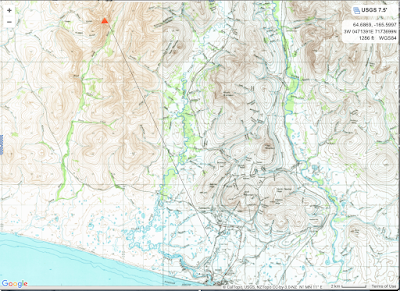

| In the process of making this map, I learned so much. Here have I spent several weeks struggling to write this work of historical fiction, and also made many wrong turns in the deep brush, just to prove my theory of a turn-of-the-century carriage road up Grand Central, and the whole time the thing was already marked on the old USGS map. I just never noticed it before. The red line (above) shows the dashed line on the old map, which must have represented the road, as near as I can tell. It seems to follow the braided creek bed for much of the way, which might explain why it's so damned intermittent these days. They must have often used the bluff that parallels the river on the northeast side because there is a road up there, too, shown by the purple line above, which represents my hiking route last July, 2017. Point A (surveyed on the map as Pt. 747, the spot in the photo above) shows the flat place next to the river in the Thompson Creek moraines where Johnson shows his narcissistic tendencies. Point B shows a spot where I once found evidence of rectangular stone walls and stone structures; it is the origin of the smoke plume where Johnson turns his back on society. Here also have I argued for the existence of a Grand Central Glacier; I believe it, too, is depicted on the USGS map above, if one zooms in close enough. |

Johnson could see a plume of smoke coming from an encampment up in the West Fork, a mile out of his way. He knew that yet another Osborn had been appointed as foreman and seen fit to move in there up the West Fork, at the very head of the whole ditch line, with yet another imported wife from Sweden. They had made tidy little homes down on the riverbed, with stone walls and chimneys of rock, a nice little domestic scene.

But after the crowds at Thompson Creek, Johnson had soured on domesticity. If he had been honest with himself, he would have admitted he was bitter that Mt. Osborn had been named after Osborn instead of after, well, himself. They didn't even climb to the highest tor, thought Johnson. Nobody but he had made the distinction of continuing along the summit ridge to find the actual high point of the mountain, and his daring ascent of the highest, crumbling tor had gone unnoticed and unheralded.

|

| The road up Grand Central is easier to follow on Google Earth than in real life. Above is a Google Earth showing the confluence of Thompson Creek with Grand Central River. Johnson is waiting outside Osborn's wife's cabin at Pt. 747 (Point A from the map above) near the top center of the frame. If one looks closely enough, one begins to see old roads leading everywhere. Such is the case when one is down on the ground as well, and delirious from hours of strenuous hiking with a heavy pack: roads, everywhere, in front of me, that line of willows, just up ahead... Was I hallucinating all these roads in Grand Central? |

Johnson was reflecting with satisfaction on how the breeze had abated the bugs, when he was struck by a chance remembrance: was this the week that teacher fellow from Nome (What was his name?... ah, Frank, another Frank, like me... wait, that's not my real name... ) was bringing a group of school kids up to climb the mountain? Johnson had said he would meet them in Grand Central. Maybe the teacher and his gang were over there in the West Fork of Grand Central right now, less than a mile away, having a merry time and singing songs around a blazing bonfire full of Wild Goose lumber. Johnson imagined he heard the trill of young voices carried on the breeze.

The thought of social interaction waiting so close at hand filled Johnson with a mixture of longing and dread. In his mind, Grand Central had forked in two: one fork led to human company, the other to solitude. The choice confronted the miner like an elemental question. But what did Johnson know of introspection? How could he have known it was his own sense of diminished self-worth that drove him to choose the fork with no people in it?

|

| A photograph by Franklin Karrer taken somewhere near the summit of Mt. Osborn, looking southeast over Crater Lake and the Wild Goose Pipeline, sometime between 1910 and 1914. Who knows, maybe Karrer or one of his students ferreted out which of the summit pinnacles is the highest and snapped this photograph from its narrow top, but I doubt it. Thanks to Laura Samuelson at the old Carrie MacLean Museum for forking this one over to me. |

Johnson stopped at a pair of glacial erratics which stood alone on the tundra, a favorite spot of his in which to practice rock climbing. He called the boulders "Sow and Cub" because he invariably mistook them for bears from far away, causing his heartbeat to rapidly accelerate when traveling without a gun, as he was now.

Johnson took off his gumboots and climbed barefoot, because that's what Perry Smith would have done, though barefoot had been more suitable for the soft sandstone of the Elba than this sharp, jagged stein of the Sawtooths. Soon, Johnson was lost in a reverie, moving up and down and sideways over the face of the free-standing boulder. The game was to eliminate holds by placing them out of bounds, thereby creating the most tenuous sequence of moves possible over the tiniest of holds.

It was an odd game, one that Johnson would never have come by in his lifetime had he not met the influential Fehrmann back at the Technicum. Not one of Johnson's compatriots in Alaska understood. They considered Johnson's rock climbing to be just another antic of another eccentric miner. Petrus called it art, thought Johnson. Maybe someday, someone will come here that understands.

|

| Erratics high in Grand Central North Fork, looking northeast. Find Lucy. |

Years before, Johnson had visited the Brenta in the Italian Dolomites. He thought maybe the limestone walls of Osborn's Northeast Cirque were just as big. Osborn's wall hid itself from the rest of Grand Central and only revealed itself after one travelled the full two miles around the curve of the North Fork.

Johnson soon arrived at the glacier. He looked up. Two-thousand feet of appalling cliffs frowned down. Loose stone coated the ledges. Horizontal bands of limestone (Johnson had always argued it should be called marble, a metamorphic rock) crossed the entire cliff, showing slabs that would require plentiful amounts of Level 0 climbing. No way. No way the Irish pensioner had passed over the northern shoulder of Mt. Osborn. Dude must have been mixed up.

|

| Looking southwest across Northeast Face Osborn. Franklin Johnson never did succeed in climbing Johnson's Tower. |

Johnson couldn't let it rest. These walls were his domain, his and the eagles. He had to know where that pensioner had gone, had to sniff his tracks and pee on them himself. Johnson knew that if he crossed the crest of Osborn's north ridge too far to the right he would end up in the Grand Union drainage, and the pensioner had clearly stated he passed over to the Cobblestone River drainage. The night was perfectly fine, with nary a breeze, and if the midnight sun did not blaze, it certainly shone. So Johnson continued up, angling across easy slopes toward a prominent limestone tower. Maybe if I climb it they'll name it Johnson's Tower, thought Johnson, but he doubted it, then grew ashamed. Only someone who had participated in the obscure cult of tower climbing in Saxony could possible appreciate the value of climbing a tower, well below the main summit in altitude and off to the side, simply for the sake of climbing the tower.

|

| Looking down at glacial remnant in Grand Union Creek East Fork. It was still a living glacier in Johnson's time, a fact he later reported to his inquisitive friend, Henshaw, the surveyor. |

He soon reached the ridge crest. The view to the north sprang open like a Jack-in-theBox. Johnson saw another little pocket glacier down below. Johnson's intention was to climb southward along the crest toward Johnson's Tower, and then along toward Osborn's summit, but Johnson quickly saw it was a no-go. The climbing was too steep, too continuous. A stone tossed off the cliff to the north did not hit bottom for many seconds. Fehrmann might have soloed along this ridge, but not Johnson. No feasible way presented itself that would allow passage to the north shoulder of Osborn. The Irish Pensioner had been spouting palaver.

Unless... unless the dude went up the low-angle gully beneath Johnson's Tower, thought Johnson. The gully didn't look too bad from down below. The sun had reached a point in the sky where it was just rolling along the western horizon from sawtooth to sawtooth, gunsight to gunsight, casting the entire mountain range in oranges and red. Johnson decided to drop back down to the glacier and investigate the gully.

|

| Looking up the couloir investigated by Johnson |

He was tired, Johnson realized. His plan had been to finish the night with a hike back to the depot, all the way out to the road where his gear was cached, but this was too far, it was never going to pay. He briefly considered going to the encampment in the West Fork, but he did not wish to inflict his unworthy presence upon the god-fearing crowd there. He'd have to siwash at Thompson Creek. Hopefully he could find a stray smudge pot lying around the camp to keep the blamed bugs away.

|

| Osborn's brooding northeast wall |

"Ja, ja, dat is wot I thought," replied Johnson. "I mean, dot is what makes sense." The southern shoulder of Osborn wouldn't be too hard to cross. Johnson felt a bit silly now for hiking all the way up the North Fork just to check out a claim he had already known was bogus.

He had slept well. The moraine had been swept all night by a breeze that blew the mosquitoes away, along with Johnson's personal demons from the day before. The smell of beans and bacon filled the air. He did not resent his coworker his erratum, and even when Johnson received an order from the Foreman to return with the trolley to the depot to pick up another load of planks for the day, he was cheerful, though the weather looked to be rain again soon.